CROWD NOISE: The Aesthetics of the Riot

1.

What should the aesthetic response to the riot be? Can there be an aesthetic response to the riot that doesn’t undermine its energy? How can the ephemeral nature of the riot be contained without becoming co-opted? Is it possible? Is it even worth the attempt?

2.

The riot, at its core, is pop. It must be populated enough to qualify as “unrest,” or “bedlam,” or “insurrection,” or “uprising.” An individual can protest alone, but—short of self-immolation—it often takes a crowd to shut down freeways, ransack public offices, interlock arms and beat back the batons at the barricades.

3.

In Equipment for Living, poet Michael Robbins writes, “A pop song is a popular song, one that some ideal ‘everybody’ knows or could know. Its form lends itself to communal participation. Or, stronger, it depends upon the possibility of communal participation for its full effect.”

In this way, the Macarena blaring over the loudspeakers at Yankee Stadium, or “Sweet Caroline” blasting at a wedding, or “Living on a Prayer” playing on the jukebox in a Jersey bar harnesses more people power than “Bulls on Parade” ever could. We can’t bother with applying aesthetic judgment to—what many fair-minded listeners would agree—are such loathsome songs. Recontextualized as shared, communal phenomena, they don’t stand to be scrutinized according to any standard metric for “good” or “bad” music. We need to acknowledge the power of the moments these songs engender, not the songs themselves.

4.

There are exceptions. The aforementioned “Bulls on Parade” certainly functioned in the spirit of the riot when it was performed on a stage outside the Democratic National Convention in 2000 and led to mass arrests. The filming of the music video for “Sleep Now in the Fire” forced the New York Stock Exchange to shutdown. The most recent example is the spontaneous cultural force of Kendrick Lamar’s “Alright” at demonstrations.

As reported by NPR, Kendrick’s 2015 “Alright” has become, if not a fixture, then an act of faith at rallies and ruptures in the fight for racial justice. It incants when the police are arresting young, Black boys in Cleveland and when protestors gather outside LAPD headquarters. Where This is what democracy looks like! and Whose streets? Our streets! can lose its luster as the masses are kettled, dispersed, and splintered by the State, We gon’ be alright functions as both palliative and rebel yell.

5.

I’ve heard some say pop music is escapism—the same for ambient. It’s a salve for the post-march sore feet, an Adderall for the after-party. For when you realize you have work in the morning and the revolution hasn’t—despite the thrum you felt hours ago—arrived.

I’ve heard people call pop music a distraction, an opium. Pop music as a blissfully ignorant soundscape for shoppers who rely on mall escalators for their scenic overlooks.

But what if pop music is evidence of a world on the brink of true, unutterable, as-yet-unseen solidarity? Pop music as devotional hymns.

6.

You can hear cops barking dispersal orders through megaphones. Sirens are wailing. There’s the low rumble of crowd noise—a din for the dispossessed. Acapellas of pop music rise from this chaos, like a balm over the shrieks and chaos. A bed for bedlam to rest its battered head on.

Could there be any better form than the acapella for the occasion? Save for the militaristic thumps of drum circles, our voices are what carry us through collective action. Shouts, hollers, and hip hip hoorays. A capella—with its origins “in the manner of the chapel”—raises those hectic voices to the level of saintliness. Voices doing the work of gods.

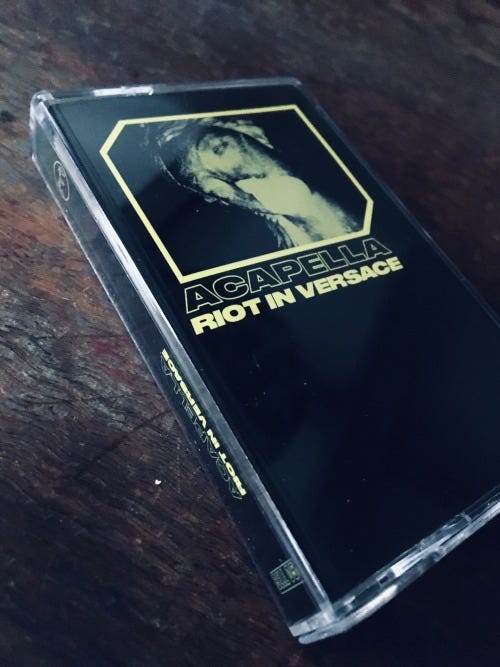

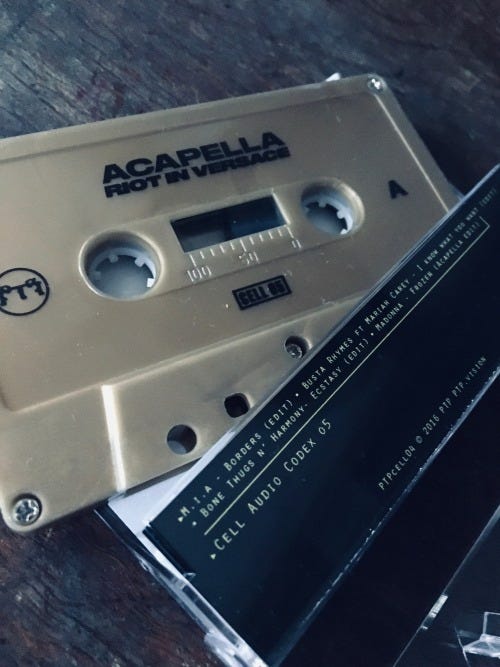

The echoes that have been added, the calm and comfort of reverb, contribute to a sense of containment. Not in the way the cops kettle crowds of protestors. The containment is in how the effects act to interiorize the ecstatic, open-air uprising. Riots are out there. They are rehearsals for the revolution, as they say. By their very nature, they refuse containment. But on Side A of CELL, Issue 5: ACAPELLA - Riot In Versace—a tape release from PTP—the sounds of insurrection are captured, contained, and packaged into a Norelco case, offered up to the masses.

Hearing Busta Rhymes’ abyss-deep voice sing If you give it to me, I’ll give it to you. I know what you want is like a concussed slumber. His voice is the one you hear when you’re coming to. Maybe you took a tear-gas canister to the temple. Riot In Versace is the Maalox running down your face to counter the agent.

7.

Pop music and protest truly makes for strange bedfellows. Nothing seems to work just right. Always contrived, or a cloak of co-optation, or a conspicuously raised consciousness. We soak in the suggestions of Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On only to have Sly Stone raucously respond with There’s A Riot Goin’ On. It’s difficult to take finger-pointing songs serious when—so often—they sell so well. The intent is belied by the result. Songs don’t change the world, but they do earn profitable acclaim.

The slurry of pop vocals sampled on Riot In Versace seems to tease this idea, toy with it sadistically. The first voice we hear that isn’t culled from a field recording of the Ferguson streets is M.I.A.’s. For all her sociopolitical pop (the vocals are from “Borders”) and guerrilla decolonizer imagery, she gave birth to a Lehman brother. The pop/protest conundrum is most apparent in her appearance beside Madonna at the Super Bowl halftime show where she breached her contract by flashing a middle finger whilst lip-syncing—the rebel equivalent of sticking your tongue out at a teacher with her back turned.

The other multi-platinum pop artists who appear on the tape are Bone Thugs-N-Harmony, Mariah Carey, and Madonna. All “edited,” according to self-proclaimed “Editor-in-chief” Geng (employing a decidedly non-musical title on this occasion), so as to foreground the People, the masses: “The youth want a better America but the battle will continue if the people remain unheard.“

8.

Geng referring to himself as an editor-in-chief of Riot In Versace signals an awareness about the limits of pop music in an insurrectionary context. The tape is more of a text (a codex) than a record.

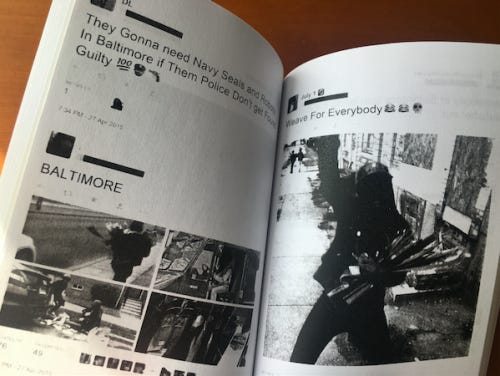

The nods to textuality remind me of another text. Where Riot In Versace documents and archives the Ferguson uprising, The 2015 Baltimore Uprising: A Teen Epistolary is a zine that captures Baltimore in the wake of the murder of Freddie Gray. It’s a text worth considering through Nicholas Thoburn’s insights, which he shares in an article titled “Twitter, Book, Riot: Post-Digital Publishing against Race.” Thoburn calls the zine an “experimental, small-press book whose content consists entirely of some 650 screen-grabbed tweets….[a] book [that] courses with crisis.”

9.

Thoburn accurately describes the role text-based documents have played in the concatenating struggle for racial justice, but he also identifies the pitfalls and problematics of giving primacy to the written word over that which is uttered:

…consider the role of Abolitionist tracts, the publishing genre of ‘slave narratives’, or anti-colonial works like Franz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth in galvanising struggles against racial violence. This is not to suggest that resistance to racism has taken shape through publishing without complication. In slave narratives, for instance, enslaved people sought to ‘represent themselves as “speaking subjects”’ toward ‘destroy[ing] their status as objects, as commodities, within Western culture’ (Gates 1988, 129). But these narratives succeeded, Ronald Judy (1993, 88, 97) argues, only insofar as they confirmed Western modernity’s principle that ‘writing [is] the sole avenue to humanity’. They hence fashioned ‘Negro’ subjectivity on the interdiction and invalidation of the ‘African’, voided of which the achieved subjectivity was ‘nothing so much as an investment in the terms of philosophical reflection: writing.’

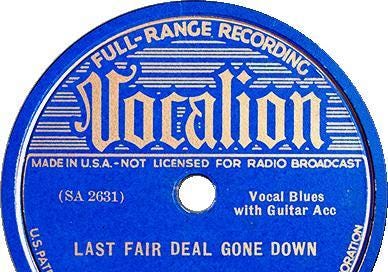

The field recordings on Riot In Versace prioritize the voice, not the transcript. The primacy of the voices rebuffs these Western conceptions of “humanity.” It’s reminiscent of how Alan Lomax pointed a microphone at Lead Belly in Angola and implored, Now sing. Lead Belly was singing even without Lomax there to capture it (re-creating Lead Belly’s captivity in another sense, one beyond prison bars). Lead Belly’s voice was taken captive—like a haint—and [o]pressed as 78 rpm vinyl records, generating wealth that would be distributed unequally. It was no fair deal going down.

10.

All this being the case, The 2015 Baltimore Uprising: A Teen Epistolary is a curious item, seeing as how it reproduces authentic voices—albeit filtered through the trappings of social media—onto the printed page. Thoburn writes:

Publishing, then, is at once a significant terrain of black resistance to racial violence and one that is fraught and ill-fitting, such that Cornel West writes, ‘the “ur-text” of black culture is neither a word nor a book, not an architectural monument or a legal brief. Instead, it is a guttural cry and a wrenching moan’ (cited in Wilderson 2010, 109).

Thoburn quotes West who is quoted in Wilderson, all of which is now quoted by me. Case in point: we are x times removed from the immediacy of bodies in the streets. Same goes for the evidence of these extempore “Alright” celebrations. Where do I see them? YouTube and Twitter. That is, social media platforms, which are nominally “social.” Re-watching these moments on the internet might be sufficient for a shot of dopamine, but you’ll still be somewhere the rupture is not. You don’t have your ear to the street, so to speak, to hear the guttural cry.

11.

The tweets that comprise The 2015 Baltimore Uprising: A Teen Epistolary are examples of what we often call screaming into the void, as social media is echo-chamber or hellscape or vacuous pit—take your pick. But when those tweets are aggregated and collated into the pages of a physical book, they gain validity: the cries are heard and documented beyond the living, breathing, ephemeral moment.

12.

Pop music often appears as a polished, manufactured perfection of sound. It’s frequently auto-tuned, edited, punched-in: overproduced. It’s what gives so much pop music its sheen. Despite all these efforts, it’s a decidedly low art, vulgar even. It stands it stark contrast to the epistolary form. Thoburn meditates on the inclusion of that term in the book title: “But it is a surprise indeed to see it [the term ‘epistolary’] naming a contemporary book on uprising, and, given its elevated cultural associations, to find it attached to the ‘low’, commercial term of the ‘teen.’”

The same high/low register play can be found on Riot In Versace, where its title, too, reflects the dichotomy—“riot” representing the low, street politics; “Versace” representing high luxury and corporatization. Thoburn provides a physical description of how Baltimore Uprising further deconstructs the traditional connotations of “epistolary.” The zine, he writes, “is a pocketsize codex, monochrome throughout, with a tape-covered spine, comprising 272 staple-bound pages, and has non-standard dimensions of 11x14x1cm.” He describes the “flimsy paper covers” and how “the degraded monochrome of its photocopies pages convey a feeling that its coherence as a complete and integrated artefact is barely achieved.”

Therefore, the humble, DIY assembly and production of this material book subverts the “classical, eighteenth-century guise” so often associated with the epistolary form.

This isn’t the works of Samuel Richardson.

The book, most simply, amplifies (or signal boosts) the voices of teen rebels—voices which are typically, historically, muted, ignored, censored, or belittled.

13.

Furthermore, Riot In Versace is a document, with all the finalization that term connotes. That particular uprising is over, done with. But is that the case? Thoburn invokes Maurice Blanchot’s claim that “political publishing require[s]…media that [can] prolong [the] ‘arrest of history’, that [can] bear and extend its rupture through their material forms.” This tape from PTP is one such material form. It is an example of “ruptural media” whose “critical adequacy to the uprising resides above all in [its] fragmentary, fleeting, and incomplete nature, in [its] ruination of totalizing, encyclopaedic enclosure.” These pop voices appear and dissipate. They mesh and layer over crowd noise and blaring-cum-bleary sonics. They’re peeled from their instrumental foundations, hovering in a no-man’s land of unruly noise.

14.

Thoburn expresses an appreciation for how the book—like any zine worth the stolen materials it’s constructed from—was originally published free from the authenticating adornments books are known for. There weren’t any credits, and there were no signs of consumerism. No ISBN. No Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data. No bar code.

The absence of interpretative text, editor’s name, and publisher details again plays a role, for Baltimore Uprising in this way blocks the passage readers would otherwise be offered away from the uprising to an anchoring authority or interpretive summation external to its tumult.

In other words, this compilation of tweets from young, Black voices on the ground arrives unfiltered by white institutional power. The same can be said for CELL, Issue 5: ACAPELLA - Riot In Versace—there is little explanation as to the sounds presented, no official production credits, etc. We assume Geng’s credit as “Editor-in-chief” means he’s the human responsible, but there’s a clear attempt to eschew authorship/ownership. (Baltimore Uprising has no official or unofficial author—no names attributed to it at all.) Geng seems to be suggesting he’s merely the arranger of the sounds, unwilling to stake a claim to this autonomous and cacophonous chorus of voices. He’s only functioning in the role of archivist. Much like whoever combed Twitter for the tweets that would comprise the pages of 2015 Baltimore Uprising: A Teen Epistolary.

15.

The aesthetics of the zine are also a focus for Thoburn. He considers it an “anti-book” (Thoburn is also the author of a book called Anti-Book: On the Art and Politics of Radical Publishing) full of degraded images of screen-grabs—xeroxed to death, martyred for the purpose of reproduction and illicit redistribution. This decision is anathema to traditional publishing and marketability. The book (or anti-book) seems positively gleeful in its form and posture:

The book’s poor-image tweets have a mocking or menacing effect on the perfect image of Twitter’s clean, unifying, and innocuous interface, that visual scene epitomized by the infantilizing baby-blue dove that is Twitter’s corporate logo. They also trouble the value paradigm of Twitter. The tweets have been appropriated, without permission or license, and, in contrast to the adtech economy of social media, the attention they attract in this book has no payoff for commercial data-capture and audience brokerage.

Thoburn also notes the pop culture references scattered throughout the tweets, one of which reads “Told Yall …GTA 6: Baltimore Trenches!,” while another reads “This better than the actual Purge Movie” which, again, speak to a communal participation, a shared understanding, a [raised] collective unconscious. As if to say, We played your video games. We watched your films. We listened to your music. Now witness us exemplify what actually matters to us.

16.

Which brings me back, once again, to Riot In Versace.

Like the degraded images in Baltimore Uprising, the pop songs on Riot In Versace are degraded, or at least appear so, as they’ve been buried in the mix under field noise and crowd static. Not to mention the songs have likely been lifted from vinyl, tape, CD, or mp3 recordings—it doesn’t matter which, really. The fact is they weren’t reproduced from the masters, the industry standard. It’s safe to say the makers of the tape also didn’t license these songs or contact publishing companies. To paraphrase Thoburn, CELL, Issue 5: ACAPELLA - Riot In Versace is less a tape about the uprising than of it.

Images:

Interior page image from The 2015 Baltimore Uprising: A Teen Epistolary | Protestors gather outside LAPD headquarters (screenshot) | CELL, Issue 5: ACAPELLA - Riot In Versace cassette | M.I.A. performing at the Super Bowl with Madonna (screenshot) | Robert Johnson’s “Last Fair Deal Gone Down” 78 | Exterior images of The 2015 Baltimore Uprising: A Teen Epistolary courtesy of Nicholas Thoburn | CELL, Issue 5: ACAPELLA - Riot In Versace cassette [2] | Interior image of The 2015 Baltimore Uprising: A Teen Epistolary courtesy of Nicholas Thoburn