FEEDBACK LOOP #8: Aesop Rock & Blockhead’s “Jazz Hands”

In a city of garbage trying to reap the harvest.

—from Float’s “Garbage” (2000)

…the scum, the leavings, the refuse of all classes…

—from Karl Marx’s The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (1852)

My work is made of reworked and transformed found objects…. These objects, the bones, the tiles, the tiny specks and leftovers from day-to-day living, are poetic archaeological elements that I see as part of a conceptual vocabulary of impermanence and memory.

—Kevin Sampson

…all run to riot…

—from Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse (1927)

1.

“Jazz Hands” is an epistle, a “love note to the whole fuck show,” because a shit show doesn’t go far enough. The letter is “postmarked from a lighthouse in the blunt smoke,” which reads like a beacon of despair. This communiqué is something dismal, from Robert Eggers’ The Lighthouse, if anything—and there’s a dead seagull in the cistern. Aesop crosses out and scraps the draft. Crumpled paper ball tossed to the wastebasket, misses. He puts pen to paper again, starting anew: “Dear Motherfuckers, I’m teetering if you must know.” Teeter is fulcrum talk—he’s pivoting, on a precipice, plank-walkin’. In a confessional mode. It’s the skunk hour as he channels Robert Lowell: My mind’s not right…I myself am hell. This is a love letter from despondency.

2.

Carol Hanisch’s the personal is political slogan has been gutted over the years—it’s become a flimsy fucking platitude in the same way “abolish the police” has been reduced and defanged to “defund the police.” But that doesn’t negate the truth that the personal is political. The personal can also speak to the political. Aesop’s been introspective, sure. The Sorrows of Young Ian, if you will. Recall him divulging his mental health struggles in documentary footage from 2002: “Sometimes I end up stressing myself out to the point where I can’t do anything.” But he’s always looked outward. On “Basic Cable,” it wasn’t just his brain that was in thrall to “the monstrous Panasonic,” it was all of ours, synapses dulled to death. “9-5ers Anthem” didn’t just chronicle his labor woes; it spoke to “we the American working population [who] hate the fact that eight hours a day is wasted on chasing the dream of someone that isn’t us.” Aesop was concerned for everyone on “Babies with Guns,” knowing the fear he had of “diaper snipers” was a shared one. Aesop Rock’s anxieties and depressive episodes—his struggle, in short—speak to our collective struggle.

3.

Aesop’s got few reasons to reenter the fray, but the innocence of a child just might compel him to do so: “Niece on the phone saying, ‘Ian you should visit more. / We could build forts while the pigs court civil war.’” A fort made of couch cushions, afghans, and clothespins might not cut it, but it’s adequate practice for the newspaper boxes, trashcans, and dumpsters she’ll spread across the city street as a barricade. Riots are rehearsals for revolution, right right? Right, right.

Aesop’s words—his incessant stacking of syllables, his breaths like mortar—in the spirit of garbology, build a sort of Bakunin’s Barricade (2015-2018). Turkish artist Ahmet Öğüt’s art “represents, inter alia, a materialization of a proposal by Mikhail Bakunin to place art works from the national museum’s collection in front of barricades.” Öğüt’s barricades are built from objects like car tires, metal tubes, plywood, police fences, and wooden stakes.

The announcement of the album Garbology arrived with something of an artist’s statement from Aesop:

Garbology is defined as the study of the material discarded by a society to learn what it reveals about social or cultural patterns. I find a lot of parallels between that and the idea of picking up the pieces after a loss or period of intense unrest…

Bakunin’s Barricade is exhibited with a loan contract that stipulates the component parts of the installation can be used to create an actual barricade “in the context of extreme economic, social, political, transformative moments and movements which engender high levels of public concern relating to fundamental human rights.” Weaponize the art, that is.

4.

Aesop appears to decline his niece’s invitation as he signs the message with cute-speak: “Miss you, miss you more.” “See you on the far side,” he adds. The Pharcyde? As the niece ages, she’ll learn that the police aren’t friends but threats. To quote Slimkid3, the blue coat billy-goats will leave her discomboburated… discomboburated… malfunctionated faded. She’ll be left with a “couple new scars in the archive.”

5.

When you take to the streets—to build barricades, to protest police violence—you’re fighting the system and the spectacle. Guy Debord told us that modern market-driven life is an “accumulation of spectacles,” and that includes the very demonstrations against such a life. “The spectacle,” he says, “is a social relationship between people that is mediated by images.” Images of pussyhats and punny signs. Images that can go viral, mine data, bait clicks, and suck selves into screens. Images that sell, sell, sell.

It’s a magic trick, really. That invisible hand that sniffs out profit with a glistening pig snout. But Aesop Rock, that Ted Kaczynski-cum-Kool Keith cenobite, is “not here to pull scarves out” of his sleeve. He’s not “here to pick tumblers underwater with his arms bound”—none of those Houdini steez. And he’s not down for the histrionics either—the “where art thou’s” of Shakespeare’s stage. No trap doors or illusions. “We don’t do smoke and mirrors,” he swears.

6.

Aesop Rock knows what needs to be done. He’s “down to throw a grapnel at a guard tower, / Down to spray piss on a cop car.” What is the role of the artist, though, in the age of a militarized police presence? Is the composition of a song a substitute for direct action? Resistance takes many forms. During the Holocaust, you could stab a Nazi in the jugular with a dull steak knife or hum a Hebrew song under your breath. Art can transgress and rile and rancor the right people. Andres Serrano can submerge Christ in piss. Dash Snow can smear semen across tabloid front pages bearing the image of yesterday’s politician. Rappers can reflect a reality too readily denied: “This pig he killed my homeboy”—word to B-Real, wee wee wee.

On “Jazz Hands,” Aesop tests the limits. His words might be “rage in the form of Renaissance art.” His song might “wake a giant” or “poke a bear.” What he can’t do, apparently, is treat this rap thing “like a job at the stockyard / And feign shock when they turn the block to a pock mark.” Aesop’s agitation then goes sci-fi. Even with “stock parts” he’s “knocking on Mach 1.” Camp Lo bumps in the system, but Aesop decides against killin’ ’em softly. He’s a limelighter—not gonna fade to black comfortably. In fact, he’s “amped up, [his] eyes glowing unknown pantones.” Colors swirl at this speed, and the scene “feels like a Van Gogh.”

7.

What happens next is something like a spiraling acid trip or a dizzying fever dream, so “bring acetaminophen.” A widening gyre that engulfs; a world turning circles. Not an innocuous or inoculating nursery rhyme. Not the fall-down descent of “Ring Around the Rosie,” but “ring around the king of pain,” which stings like a black-spotted sun, alluding perhaps to “King of Pain” by—you guessed it—The Police (as in, Fuck the). Dyslexically, the sequence of “[king of pain, / Bring]” leads us to Method Man, so let’s go inside the astral plane.

Adrenaline-fueled, Aesop possesses a “new super power that [he] picked up in the frenzy.” He’s able to manifest phenomena with only his mental: he “could draw a roof on fire from memory”; “each and every sketch another bloodletting.” Drawing the fire; sketching the bloodletting. The art acts up—it agitates.

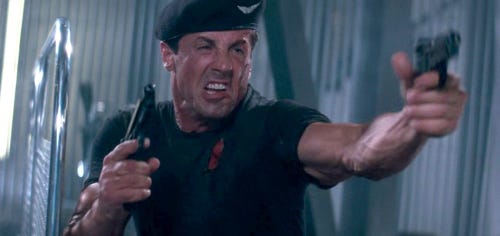

This isn’t solitary work, though—it’s an invitation to collective action. RSVP has two box options to checkmark: “either you see the vision or dinner demolition men.” And he asks without a Stallone slur, so you know where he stands. The dual meaning of “demo,” too: the activists who organize a demo[nstration], and the cops whose actions incite the demo[lition] of a downtown.

8. “I had to do something to let them…know I still exist.” —Cornbread

Is there nothing more pathetic than cleaning up graffiti? In the wake of George Floyd’s murder in May of 2020, residents in Minneapolis volunteered their labor to the likes of Chase Bank. They scrubbed away the “vandalism” which had come to adorn the windows and walls of the financial institution. Performative community care for the masses. The revolution will not have jazz hands. Don’t they know Chase Bank accepted slaves as collateral on loans to plantation owners? Don’t they know JPMorgan Chase targeted Black homebuyers and sold them on garbage loans in the aughts?

9. “Dwellin’ in the rotten apple, you get…caught by the devil’s lasso, / Shit is a hassle.” —Nas, “The World is Yours” (1994)

I step into the room, split an arrow with an arrow.

The first trick shot is just to show ’em that I dabble.

I will not be aiming for the apple.

Aesop Rock angles in as a folklorist. Less William Burroughs; more William Tell. Appleseeds burst with a cyanide splash. Thanks for nothing, lowlife. We sometimes forget the rapper’s namesake. “Long Legged Larry” seems innocent enough, but even Aesop’s Fables includes one about a “treacherous Frog” who ties a mouse’s leg to his own with a “tough reed” and drowns the rodent.

Counterrevolutionaries, a.k.a. Little Ed Kochs, will buff the trains and put “razor-wire fences and guard dogs” in the yard, according to Jeff Chang. Koch fantasized of worse: “If I had my way, I wouldn’t put in dogs, but wolves.” Is that a dog at the front door barking at the air or a “wolf at the door like a bug to the fructose”? Who the fuck knows? But that wolf will soften his voice, don grandmother’s bed-clothes, and swallow that Little Red Riding Hood whole.

10. “The idea of digging through old, neglected music from another time with an ear tuned for taking in that data in a different way…is exactly what Block does.” —Aesop Rock

Blockhead digging through record crates is like A.J. Weberman fanatically rummaging through Dylan’s trash cans in Greenwich Village. Block conjures the spirit of a junk sculptor for his assemblage of swirling sonics. “Waste makers provide the conditions for scavenger art,” Donald Clark Hodges wrote in Artforum in 1962.

Blockhead has been a web crawler for decades now, collecting the detritus whether it’s dope or dum-dum, compiling a cache of useless images and temporary internet files—meme litter. As Joseph G. Schloss has pointed out, beat diggers “seem to be predisposed to collecting things in general.” If you dig in crates, you get dusty. Dusty connotes not only the dinge of the external world but also the cloistered sedentary life of computerized time—the dedicated tinkering upon monastic musical machinery—that creates a layer of dust only to be countered by cans of compressed air. If you’re a digger, you find yourself in storage facilities: garages and thrift shops and swap meets and hoarderific record stores. What’s beatmaking if not woolgathering? The production on “Jazz Hands” sounds like someone caught in a looping meditation.

“The idea to go with no drums over the verse was Aesop’s,” Block says. Liberated from percussion, Aesop’s flow is irregular, slowing and accelerating according to attitude, not time. “It’s very much a regular 4/4 beat,” but the vagabond variability of Aesop’s voice makes it seem otherwise. Blockhead describes the production as possessing “this feeling of swelling waves…as the layers weave in and out of it.” I can’t help but Google image search photos of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, a trash vortex of marine debris, of horizonless plastic waste broken down into small particles, like a 2.5 second loop, like the 12-bits and 10.07-seconds of an SP sample.

11.

Comfort can be found in confrontation, in “going from being chased to playing chicken.” You don’t need healing crystals and a zodiac chart to “treat every interaction as a living wake.” That’s just good common sense. Look around, one might say, “before the photo pixelate,” before the seas rise, before the horns blow. You’re liable to “get your whole road map Pac-Man’d.” Moral compass gone zany.

12. Black mask.

The black mask is likely a balaclava. Slip the surveillance state. Scramble the facial recognition software. The black mask is a skeleton key, a vortex to meaning. Aesop’s “Dear Motherfucker” greeting might just be an address to Ben Morea. After all, Up Against the Wall Motherfucker, or UAW/MF, or simply “The Motherfuckers,” began as Black Mask. They havocked the streets of New York in the 1960s with Situationist-inspired antics and exploits.

One such action involved gathering the city’s refuse as sanitation workers went on strike for better wages and safer conditions. (“We may handle garbage, but we’re not garbage,” as one Local 831 sanitation worker put it.) The Motherfuckers plotted. They hauled the rotting garbage from the Lower East Side to the philharmonic, operatic, bourgeois steps and fountain of Lincoln Center, to its gala-goers and elite society sirs and madams in their tuxes and ball gowns. The filthiest rich. The Motherfuckers, to paraphrase Hodge, “[exposed] this waste to public view by focusing attention upon it instead of hiding and disguising it…. exploding the illusion that ‘dirt’ no longer exists.”

The action was documented in 1968’s Newsreel short film. We throw garbage on them. We puke on them. We say fuck you to them, the narration says, symphonically.

The anarchists leafletted, too. WE PROPOSE A CULTURE EXCHANGE: (garbage for garbage), the title read. “America takes all that is edible,” it continues, “exchangeable, investable, and leaves the rest.” Like space junk. Like Gargantua and Pantagruel’s table scraps. (Aesop Rock really is rap’s Rabelais, what with his excess of words, philosophical slants, lurid folklore, and undiluted fun.) “The world is our garbage,” the Motherfuckers explain. Music and art—“Beethoven, Bach, Mozart, Shakespeare”—only function to “cover the sound of our garbage making.” They sum it up in a sordid sort of haiku:

A cultural revolution

garbage fertilizes

discovers itself

13. “The revolution will not be jazz hands.”

In this percussionless mode, Aesop is proto-rap—a conduit that channels Gil Scott-Heron and Gary Byrd. We need to know revolution is not Pepsi can handoffs to riot cops. “It’s not an ad, hashtag, or a tap dance.” Revolution is not an IG influencer posing for a planned and premeditated photo opp curbside during a BLM protest. An “influencer” who wouldn’t know an anxiety of influence if it panic attacked them in a comments section. Such gestures are “alien to matters of the heart and mind.” Meanwhile, the rest of us “park the car and scream into the dark of night.”

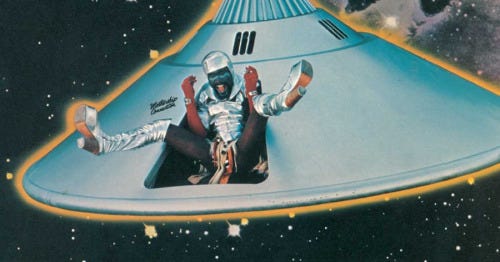

“Jazz Hands” argues you can both be on the barricades and planning an escape. When Aesop Rock talks of taking “a rocket to the Kármán line” and proceeds to the countdown, it’s not some billionaire blastoff. He’s talking of tearing the roof off the sucker, a P-Funk diasporic trajectory. An extraterrestrial alternative to the lifeless landfills of Earth. Some space shuttle orbiter with a Sun Ra rattle. A soulsonic blast with excessive force.

Images:

“Great Pacific Garbage Patch,” Ethan Daniels/Shutterstock.com | Bakunin’s Barricade (Istanbul) 2016, Ahmet Öğüt | “The entrance of Lycee Dorian high school in Paris was blocked with rubbish bins during the protests,” Geoffroy van der Hasselt/AFP/Getty Images | Harry Houdini Jumps from Harvard Bridge in Boston, Massachusetts, John H. Thurston (1908) | Demolition Man, 1993, dir. Marco Brambilla (screenshot) | Citizens of Minneapolis cleaning up graffiti off Chase Bank (screenshot) | Up Against the Wall Motherfucker, Berkeley Barb, courtesy of Sean Stewart | Newsreel, 1968 (screenshot) | Parliament, Mothership Connection, 1975 (detail)