DEBRIEFING: 10 January 2025 | Brooklyn, NY | Elsewhere (Zone One)

Notes on rappers hollowed-out and not, worldconvergence, and the passing of Dax Pierson

I.

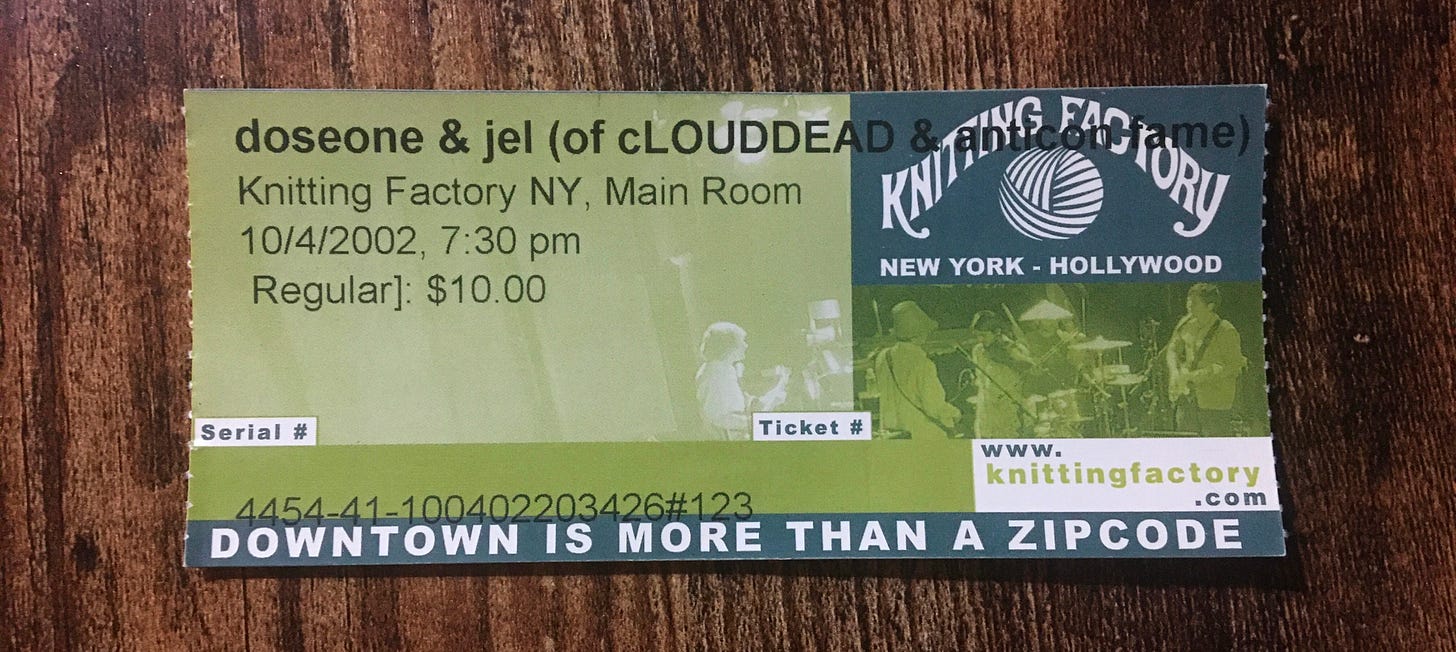

The last time I saw Doseone onstage was October 2002. It was at the erstwhile Knitting Factory location at 74 Leonard Street. He was performing with Jel and Dax as Themselves—ironically and spiffily outfitted in suit jackets and ties—touring The No Music, playing the full album, from neck to nethers. The stage was adorned with keyboard synths, drum machines, samplers, and an easel for propping up a stack of placards—my favorite of which warned of placing children in Tupperware. For those who don’t know, Doseone is a showman, and he always has been. His stage theatrics, spastic gesticulations, wild gyrations, and histrionics that hem and haw between hypermasc and homoerotic valences are, simply put, some hype shit. Dose swerves in a psychotic neurotic mode—he stunts, never fronts, and hip-hops: authentically, factually, self-actualized.

On Friday night, Dose marauded the floor of Zone One at Elsewhere in his multi-patched bomber jacket. At the invitation of headliners ShrapKnel, he arrived in NYC for a show, fortuitously, on the occasion of his Backwoodz debut: All Portrait, No Chorus.1 Three-thousand miles away, Los Angeles continued to burn (the latest return of the “infernal season,” as Mike Davis once called it—this time somehow worse than ever—a city “shrouded in acrid yellow smog” and ash and embers), but in New York, it was brickly bitter—the whole damn week having been cold-snapped in half: lips cracked | scaled skin | dry as dead man’s bones. Dose eventually settled in, cold-lampin’ during blackchai’s opening set. With his baggy raggedy jeans and thrift-and-cut 2000 Subway Series tee, the New York emcee looked plucked from Hype!, but spit like an autonomist over August Fanon fuzz pedal production. His breath control seemed unbothered despite having only just recovered from walking pneumonia, and NAHreally leaned in to tell me chai’s voice was heaven-built to cut through the mix when performing live. He wasn’t wrong.

Steel Tipped Dove, proprietor of the absurdly prolific Fused Arrow Records, produced the entirety of All Portrait, No Chorus and backed Dose onstage. Dove hipped me to the album last summer, and when I remarked on the moves Fused Arrow has been making, he told me, “Yeah, but we’re gonna go through Backwoodz for the album—Dose is too big for us.” Truth, because Doseone is a legendary figure, as Fatboi Sharif said during his sozzled introductory remarks. Of late, Dose has found himself—like other legends of the late ’90s and aughts—floundering in a sort of purgatory for the underground rap renaissance we’re in. But he’s found a home with Zack Kasten’s fresh, wild, fly, and bold boutique label, Handsmade Collective. And Dose’s fanbase remains as devoted as ever.

Honestly, I arrived at Dose’s set expecting to sit shiva, expecting a funeral mass. Dax Pierson, Dose’s longtime friend and collaborator, died less than two weeks prior. Dose acknowledged Dax’s passing from the stage (alongwith Ka’s, Saafir’s, and Alias’s) after “Inner Animal,” and, later in the set, he explicitly addressed a personified scythe-and-shrouded Death, sick of his despicable shit, telling him to “suck his dick.” But his performance was madcap even if the undercurrent was one of mourning, one of remembrance. Retrace history with me, momentarily, as I take it back to that 2002 Themselves performance at the Knitting Factory where Dose pronounced a different kind of death: a genre death.

II.

On “Good People Check,” whose working title was at one point “The Rapper Shallow,” Dose emerges from behind his wire-cluttered gear podium to deliver a diss track abstraktion, “a dissong absolute,” a song with targets both specific and generalized—a “quitter’s anthem,” wherein Dose delineates This is why you should quit. Dose explores the cavity in rappers’ chests where their hearts should be pumping blood and volume, but instead they “sound hollow.” Dose is as direct as he’s ever been, prosaic even: “This upsets me.” He claims that “you can tell a lot about a man from the sound of his music,” and Dose tells it all: “Frankly, you’ve become suckers.” He has only one [gr]image to offer: Shove that gun up your ass—you’re as good as dead.

During the Knitting Factory performance, Dax plays keys and backs Dose on vocals—he grooves and head-nods and is full of so much feeling. On the album version, Dax handled the disemboweling bassline and Wurlitzer, dutifully/beautifully. The so-called “quitter’s anthem” is, in fact, a lamentation. “My rotting tape collection—be still my beating heart,” Dose falsettos, but there’s nothing false or insincere in his wailing, “Now I buy one new rap CD six months apart.” It isn’t a self-imposed moratorium; it’s an in memoriam dedicated to how fruitful and unfettered rap music used to be. “So I rap with a passion and stock rap at a record store,” Dose says2—persevering against all odds in his art and his labor—but, alas, “you make [him] embarrassed for both.”

Finally, Dose challenges fin-de-siècle rappers, but it’s more an invitation, availing them of an act of redemption: “Come see me, I’ll serve you, give you free music, and step.” He knows they can’t save themselves, but he’s offering to do the grunt work. “It was nothing,” he says, quoting Guru, only to cross out Gang Starr’s get a rep and scribble in, “We did it just to save our rep.” Dose’s impatience with hollowed-out rap acts presaged the underground’s downward trajectory into a hellish den of Death and Debt—vinyl records and CD plastic junkyard-bound. He saw the writing on the wall, and it wasn’t any sort of wildstyle at all.

Just over three years later, on February 24th 2005, Dose, Jel, Dax, and the other members of Subtle endured a harrowing accident while traveling through Omaha in their tour van. A black-iced Iowa road interrupted their route to Denver. Dax Pierson would never fully recover from the injuries he sustained, in part due to a defective | fuckd | faulty Ford seatbelt. What followed was millions in medical bills, pains and sufferings, expenses enough to end hope. But Dax dealt in devotional love that no fragmented and eventually fused vertebrae could slow. To be queer, gifted, and Black—and you think quadriplegia could compete? Like Nina Simone sang, Dax was left with his soul intact. Like a pause-tape production, any paralysis of spirit was only temporary. It would loop on.

III.

The Subtle crash wasn’t the first. To usher in 1999, Dose, Yoni Wolf, Odd Nosdam, and Jel traveled north to Minneapolis to perform at a Rhymesayers showcase on New Year’s Eve. They met Andrew Broder for the first time, who provides turntable work on All Portrait, No Chorus. On the way back to Chicago in a car Jel borrowed from his mother, they hit black ice, blew out their tires, and crashed into the median, nearly hitting a tree. The accident brought them closer; they coalesced around each other. The experience helped solidify the seriousness of cLOUDDEAD.

Five years later, in 2004, Dose and Yoni Wolf seemed to divine the accident that would befall Subtle a year later. On cLOUDDEAD’s “Dead Dogs Two,” Adam and Yoni (“undeceased’) trade lines, then words, then speak in unison, identifying with what they perceive as two dead Oakland dogs:

We secretly long to be some part of a car crash,

Long to see your arms stripped to the tendons.

The nudity of swelling exposed vein

webbing the back of your hand.

To be a red-tendoned dog,

To be red-tendoned dogs

blood-breathing by the side of the highway…As the car crash fiberglass dust straight-up settles on your raw muscle tissue.

“Subtle formed because of Dax,” Dose once told The Believer. “He has always been the glue that holds the band together. Dax is who each of us in the band try to think like when we try to think like a Subtle member.” Dose then, in light of Dax’s death, will have to acclimate to possessing something of a phantom mind going forward: Dax’s voice reverberating within skull and singing within skeleton. In a way, it’s a Second Death. The trauma of the tour accident and Dax’s struggle to live within the limits of an ableist world—pushing against, pushing against—was immortalized in song once already. Themselves’ 2009 album CrownsDown included “Daxstrong,” a song—an ode even—to Dax’s eternal influence. Dose, ever since, has tempered his records and efforts to honor Dax’s arm…arm…arm.

“Daxstrong” speaks to the vulnerability, margin-living, and precarity embedded in the very practice of making and performing music—futilely pursuing “art” in a society that forsakes it at every turn. Dax was symbolic of that sensitivity, and the tour accident—which occurred while the band was sleeping—cut through flesh and fantasy. “None of us ever thought that the pursuit of our dream world and dream earnings would cost so highly,” Dose once told Tiny Mix Tapes. “[T]hat there was more to take from us…who honestly give for a living…it did not taint the world for me…it proved [its] edge was actual.”

“Disability is dangerous,” writes poet Jim Ferris. “We represent danger to the normate world, and rightly so. Disabled people live closer to the edge.” Dose has always fixated on the fragility of existence, the lack of foreverness. He’s been singing a dead cat blues damn-near his whole career. “Daxstrong” functions as an utterance of the gamble:

This is cards that Earth will deal to those who teeth behind the wheel,

to those who spent their off-days up against the dent of rent

and twisting somethings from theNothingMuch and meant

to prove the wage does not the worth of men withhold.

This goes to those who feed their hands and whole

to 15-passenger vans and roll atop the black ice

like there was no god or rights in all the wrong

that showed them swipe of the slow sickle

and left you to the No Music of Hospitals.

When Subtle, like so many other touring bands, “feed their hands and whole” to the hellmouth “15-passenger van,” they lay their necks down and listen for the “swipe of the slow sickle.” Others hide their vulnerabilities, but disabled folks, much like artists (not to suggest a strong equivalence), are more likely to display them. That vulnerability is an “essential part of being human,” Ferris says. Dose’s invocation of “the No Music of Hospitals,” harkening back to The No Music and “Mouthful,” presents the Hospital as antagonist, the Medical Model menace. In Jim Ferris’s The Hospital Poems (2004), the poet critiques the “...cold-eyed / White coats trained to find your flaws, focus on failings, / Who measure your meat minutely.” That’s a quote from the poem “The Coliseum” masquerading as a Doseone lyric. The aforementioned dead dogs, you’ll note, emerge “glowing on the Oakland Coliseum green seats wasteland.” But aside from that superficial commonality, Dose utilizes what Ferris calls “crip poetics” in the Subtle oeuvre. Dose and Dax transfigure into what Ferris calls “The Enjambed Body”; for them, it is the ExitingARM. “The pit and alabaster ascension,” Dose once called it, confiding in Mosi Reeves. Reeves, meanwhile, clarified it as a “cryptic image of an immortal appendage attached to a dying body.” We’re flailing, folks. We’re all, and always, flailing.

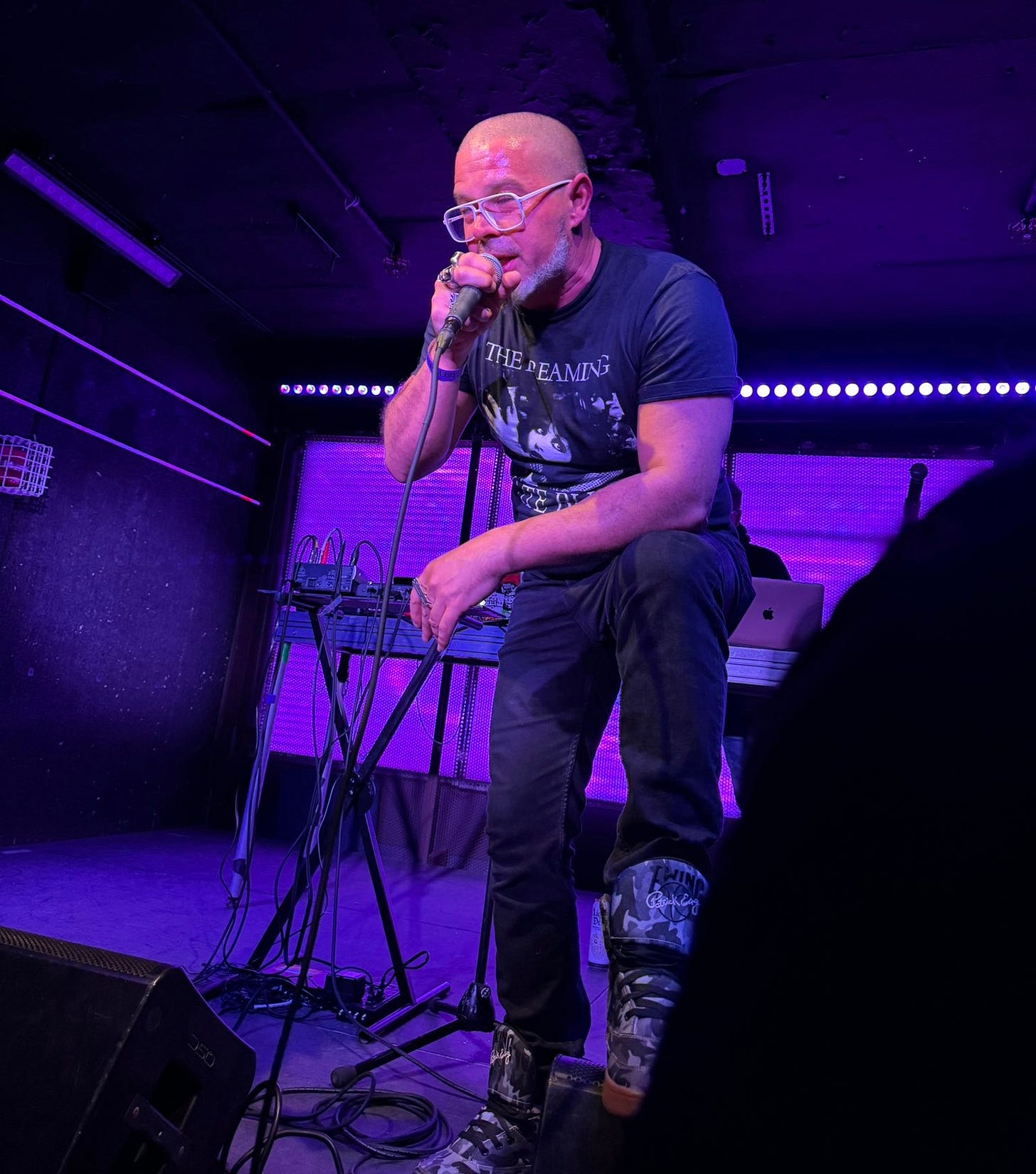

So even though Friday night in Brooklyn was a celebratory, even raucous, affair, I received what Dose did on that stage at Elsewhere as a memorial, as an elegiac performance-poem. Death was stalking in his big black boots, but Dose stepped right back to him in his camo Ewing Athletics. “So, uh, I got good news and bad news—what do you want first?” he asked the crowd between songs (Dose has also always provided beneficent stage banter). “Bad news: there’s no God. Good news: there’s no God. So live your life; there’s only death.”

Later, after “Epinephrine Pen,” he’d tell a tale of almost dying by a swarm of bees as a youth. We’re not talking about Wu affiliates either; we’re talking venomous stingers injecting melittin into the children. (Rest in Power to Thomas J. though) The Themselves show in 2002 ended with The No Music’s hidden track jingle for the Albert Brown Mortuary. Dose appreciated his Oakland apartment’s proximity to the local morgue, daily walking past its neon sign and imposing clock, which, Dose explained, was there to say, “Anytime…don’t forget!”

IV.

He hadn’t forgotten on Friday night. Adam Drucker, griefstruck, rapped with a passion. Though he doesn’t stock rap at a record store anymore, he covets his rotting tape collection, his promo copy of Boxcar Sessions that he besieged from a Philadelphia vendor. He’s rapping with renewed urgency. In this epoch, Dose raps as though through a stoma at the site of his Third Eye—centered but decentering still, entering dark matter dungeons: shook ones. We get low- & high-pitch Dose | screech & growl | dream-sharer whisper & barbaric yawp. His white frame glasses—in a Darryl McDaniels inverse—are on, then off. He goes handsfree, maneuvers the mic stand | finger-guns to his temples | push-button & chest-puff. Other times he grips the mic like Kool Keith on Ultramag’s rare groove “Grip the Mic” as he mounts his foot on a monitor:

Well I’mma grip the mic, grab the mic, hold the mic,

snatch the mic, switch the mic, freak the mic,

sneak the mic, rock the mic, eat the mic,

beat the mic, pack the mic, freak a style,

use a style, hyper style…

Dose tossed his beanie when he mentioned his “hat in the wind” on set and album opener “That Work,” alluding to The No Music’s “Hat in the Wind.” [Do you get it yet? It’s all one, long song—circuitously sent and received.] The songs on All Portrait, No Chorus sometimes sound like a dispatch from that zebraic-faced aspirant, Hour Hero Yes (who Dose once defined as “a triumph of life over death”). Other times, these selections sound almost Hemispheric in their rhythmic relentless intensity—Dose bronchial cleansing and keeping etherial downtime.

In lieu of Open Mike Eagle’s guest verse on “Went Off,” Dose broke into the first half of cLOUDDEAD’s “Dead Dogs Two,” rapping it rather than singing it:

From the height of the highway onramp we saw two dogs, dead in a field,

glowing on the Oakland Coliseum green seats wasteland—

dogs we thought were dead.

They rose up when whistled at, rib cage inflating like men on the beach being photographed.

A guard dog, for what? FOR WHAT?

He screamed the repeated For what? and its shrill screech was gut-felt. “You have to stop the blood to your head,” he finished, “to fit the death in front of you.”

Looking back but pressing forward, Dose shouted out old friends. He gave special recognition to Bookworm who was in the motherfucking house, Dose’s friend from way back who blessed the bilingual intro to the first Them[selves] album. “Whoever believes in you later when you’ve done stuff,” Dose explained, “it is nothing compared to those who believe in you when you’ve done nothing yet.”

On “Untouchable,” Dose insists—contrary to O.C.’s saying so—that “rappers are not in danger.” Not in danger of his wrath or endangered. Underground rappers in 2025 are thriving. Many might eventually hollow out, necessitating another “Good People Check” check-yo-selfing, but, for now, their hearts pump blood. And so as Dose led a call-and-response on the closing refrain of “No Cops,” a song that had been in the open world for less than twenty-four hours, he still managed to elicit shouts of “I don’t need ’em” for cops, dogs, gods, friends, meds, and regrets. Sucker MCs were left off the list. Not to say there wasn’t a battle drill swing at certain moments in Dose’s set. He closed with a cover of Saafir’s “Hype Shit,” inviting PremRock and Fatboi Sharif onstage to speak the trash-talk adlibs. “I’m not going out like a punk,” Dose rhymed as he rapped the Saucee Nomad’s defiant words.

V.

When the Subtle tour accident happened, the fractured and factionalized underground hip-hop community came together. I even remember El-P—despite the beefs, battles, and blown-up relationships of the previous years—vocalizing support and encouraging others to donate to Dax’s recovery fund. Attitudes in the underground have adjusted in the intervening years. Two decades of rappers going gray and to therapy has done wonders. For the most part, we’re drinking Zima and singing “We Are the World.”

This new era of community within the U.R.R. [Underground Rap Renaissance, my G] was typified last June at the ShrapKnel Nobody Planning To Leave album release show, specifically outside the venue where a cypher joined underground heads of past, present, and future. That cypher—it should come as no surprise—was initiated by Doseone. After album releases by k-the-i??? and now Doseone, Gary Suarez has likened Backwoodz Studioz to the late Mush Records, which boasted an alt-/art-/post-rap label roster that was largely curated by Doseone a quarter-century ago.

The crowd at Elsewhere—especially during Doseone’s middle set—was a mixed crowd. Fans he’s acquired over his years of activity mixed with a staunch Backwoodz fanbase less familiar with his work. Some will be young enough to listen with unbiased ears, while others have been around long enough to hold his Anticon ancestry as a mark against him, collectively punished for sins long atoned. Anticonworld producers like Controller 7 and Andrew Broder have forged Backwoodz connections—Controller 7 with his ShrapKnel collaboration and Broder with his sporadic production credits for woods and ELUCID. The worldconvergence, as I call it, has already made strides, and Dose signing on is a significant next step.3

But it may be the younger, nonpartisan listeners that prove to be the more immovable of the groups. I’m reminded of Slug’s analysis on “It Goes” (2001): “See, me and you, we on different pages, / We’re in different stages, / We’ve got different favorites.” After all, it was only last month that I stood on the packed floor at Warsaw and witnessed the Juggaknots put on a surprise performance while a contingent of the Backwoodz fanbase watched unaffected. With that in mind, Dose’s crossover potential, through no fault of his own, remains to be seen.

Doseone has serenaded us with quitters’ anthems for nearly three decades, striving to hold rappers to a higher standard, but he himself has never quit. He’s quit touring, yes—quit booking agents, quit managers, quit press agents, quit the industry rigamarole—but the music has never stopped. On “Best Metric,” the All Portrait, No Chorus closer, Dose humbles himself as “simply a poem-perfecter and fierce fan of rap’s nectar for as long as [he] can remember.” Nerve Bumps (A Queer Divine Dissatisfaction), Dax Pierson’s 2021 solo album, lifts its title from Modernist dancer Martha Graham. “No artist is pleased,” Graham said. “There is only a queer divine dissatisfaction, a blessed unrest that keeps us marching and makes us more alive than the other.” Doseone keeps marching. He is blessedly restive. With his New Mexico wind-weathered face, his snowy beard, and his wisdom, Dose repeats for emphasis at the end of “Best Metric”: Being the best and being a success are not the same metric. Keep seeking, reader.

Doseone setlist:

“That Work”

“Restaurant Not”

“Went Off”

“Ta Da”

“Scales Sway”

“Inner Animal”

“Untouchable”

“No Cops”

“Wasteland Embrace”

“Epinephrine Pen”

“Best Metric”

“Hype Shit” (Saafir cover)

An insight from PremRock: “Elsewhere emailed me and proposed 1/10 out of the blue. Well, I suppose due to the recent accolades and [ShrapKnel] playing Warsaw [with billy woods on 12/7]. I didn’t actually know [Dose and Dove’s] release date but knew it was in January. Dose was a random eureka thought, [and ] I had no idea he’d do it. I asked Dove and he said, ‘Well, that’s our release date, so maybe he will,’ and behold…”

Like Dax Pierson and a number of other Anticon musicians, Dose worked at Amoeba.

If we want to be particular about things, Dose connected with Vordul Mega, an early member of the Backwoodz roster, way back in 1997 at Cryptic One’s parents’ house in Westbury, Long Island for a collaboration with the Atoms Fam. But that was, technically, before Anticon, before Def Jux, before Backwoodz. Antediluvian shit.

Phenomenal piece of writing. You should write a whole book about anticon’s legacy…

Beautiful as always. I was there. Gave Dose a big hug and told him he was my hero. Gave Sharif a hug and told him I was glad to be his Union County brother. Gave Zack from Handsmade like fifteen hugs and my adoration for what he's doing. Gave Prem and Curly hugs and love as well. Gave Curly $40 for nothing, wish I had $40 for Prem... That's next time Prem, if you're reading this. 💖