Return to the Teknohell

95 Defragmented Rap Theses on Sunmundi & Sasco’s "Contacting"

I was buzzed from the contact…

—Slug, “Ear Blisters” (1995)

I opened my phone and saw the whole world before me—

it’s a gory story….

—“The Whole World (SOS)” (2025)

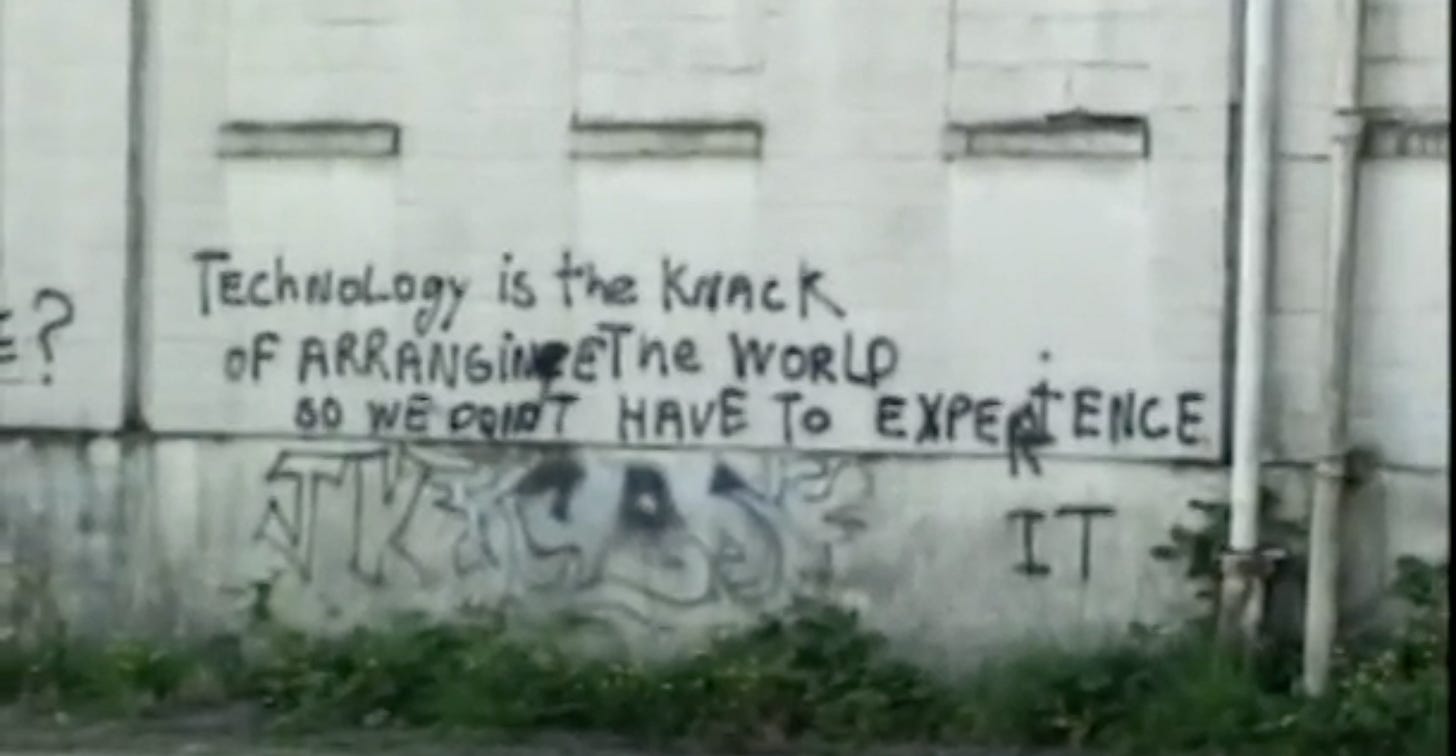

People are unaware of the extent to which they’ve been inter-penetrated and co-opted by their technology.

—William Gibson (1999)

////INTRO[CON]DUCTION////

Sunmundi’s a man apart. He works at a measured, nearly metrical pace. Where others press on prolifically, Sunmundi is particular with what he’s willing to share with the sound systems of the world—a discerning selector. He’s a New York rapper, true, but a New York State rapper, far from the madding crowd of ENYCE. Not a denizen of the metropolis. He’s married, monkish when it comes to the frequency of his performances, and, notably, more offline than most. “To embark on a project that is set in the present,” Kodwo Eshun once wrote, “you have to renounce digital abundance by undergoing a temporal diet or media famine.” Contacting, which we’re reading multitudinously—as hyperconnectivity, as alien communications1, as the sloppily soldered surface of a circuit board—sounds like a mechanically assembled mitral valve; Sasco’s sonic strategy a sort of lub dub narcotic sound system.2

Online is awful; offline inspires awe. “Oh, material world,” Sunmundi says at the start of “98 ’til Infinity,” “the sun turned on and the Earth twirled…the Earth twirled…” Sunmundi, working within his usual mode of inflection, resonates with desperation. He’s no Desperado, though he will walk across the sun barefoot looking for shade. Perseverance Rap | Severe cadence | against Austerity and all Odds/Opps. The fact of the sun “turn[ing] on”—like a light switch, like the pull-chain of a bare bulb, like the dome light in the 2013 Volkswagen Passat that Sunmundi recorded his vocals in—indicates an idea born. There’s even the subtext of the sun turning on throughout time zones and erogenous zones. “I live in the zone,” he soon says on “Bright Moments,” sounding like woods declaring “I live in my mind” on “Asylum.” But, if anything, Sunmundi’s asylum is like Tarkovsky’s Zone. The sun “blew a fuse,” Self Jupiter raps on “When the Sun Took A Day Off and the Moon Stood Still” (1999). Another new day brings another new idea. The sun and the moon in concert like the lexical blending of our man’s very name [sun + moon]. We sense the interference of the sun’s radiant energy racking our brains in the syzygy of the line:

Oh, material world,

the sun turned on and the Earth twirled

When Souls of Mischief spelled out how they chill from ’93 ’til—talking of how their talent overpowers, how brothers can’t hack it, how they’re adept at kill[ing] all that wack shit—they had no way of knowing someone like Sunmundi would receive the signal and “hack” hip-hop in his own historical moment. The final digit of the 1993 designation becomes the completed lemniscate with Sunmundi’s 1998 redux. Sasco’s production—often manic but never far from melodic—features heavy delay, horn swells, percussive accents, and brashy woodwinds and brasses. When McKenzie Wark published A Hacker Manifesto in 2004, she described hackers as “abstracters of new worlds.” “We produce new concepts, new perceptions, new sensations,” she wrote, “hacked out of raw data.” In this conception, Roy Christopher writes in Dead Precedents (2018), hackers “push their chosen technology to its limits.” Sunmundi traverses worlds ruined & renewed. He mostly remains Earthbound, of the “material world,” of a dialectical materialism that diagnoses ELUCID’s “dystopic visions.”3 He’s living in a material world and he’s a dematerialized eMCee. Lived and born in 3030 where, like Deltron Zero said, he’s feeling like a ghost in the shell.4

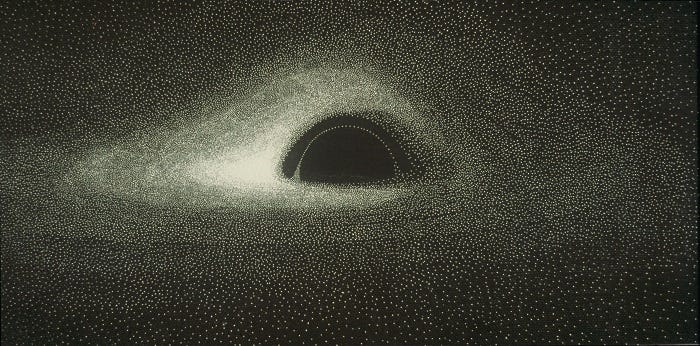

But, as we hear on “Bright Moments,” Sunmundi is dead set on dirt. “My hip bone connected to my thigh bone,” he raps, reviving “Dem Bones,” structuring his own skeleton. Later, he details how integral these bones are to the mix. He writes “down to the bones” to “make broth” on “Idling Nowhere” and sacrifices his “own bones in the brine” on “Spirit Ballistics.” Ossified concoctions. Even his neural pathways bend peatward: “Brain connects to the ground I stand on.” If we are what we carve, as he argues, then we should remain grounded in materiality. Sunmundi’s syntax makes it so: “I’ll write it in bold, bronze and gold, / Fight for the sliver of light posed vs. black hole.” Sliver scans as “silver” to slip between the “bronze” and the “gold,” metals extracted from [how about some hardc]ore. Sunmundi asks us to shape ourselves into being, the so-called “light posed” against the inescapable event horizon of a “black hole.” Vocals and production create a dense, dulcet noise wall. Sasco builds layers of spiraling, alien clickings. Again, a horn carries the beat, and each beat’s a locked chamber of echoes.

Combining the hard-won wisdom of Ka with a heavy mentality characteristic of late-career Killah Priest, Sunmundi wanders where the gravel street meets the celestial, which is the word Rob Kuehl of The Next Movement podcast has used to describe Sasco’s production. Just as Killah Priest felt “108 celestial stems stretch out [his] terrestrial limbs” (“Energy Work,” 2013), and just as he spoke of how the Sky God “travel[ed] in celestial pods of bright stars” and birthed children who built “a technology brilliant” (“Gods of E.din,” 2015), Sunmundi explores the convergence of the above and the below. But Sunmundi’s not concerned in the slightest with Elohim and Nephilim; he’s bending his own Genesis into being.

Sunmundi’s divine authorship, his Darwin of the Darc Mind, begins audaciously:

One might consider this the first flow in the whole zeitgeist.

He got that microorganism in him—

leapt out the water, grew legs, and landed on ice.

Skip to a gif of Nietzsche dunking on Jesus Christ,

Starbucks collab with Nike,

who playin’ Creator like Fisher-Price?

Restructuring the Evolution of Man as a Homo crepito [“rattling, clattering, clicking man”], where the holotype displays nothing but scams, spam, AI slop, and brainrot, he delineates precisely how far we’ve come | how far we’ve fallen. It’s essentially a more detailed portrait of what woods went for on “Year Zero” (2023): “Apes stood and walked into the future, / March of Progress end hunchbacked in front the computer.” Instead of Rudolph Zallinger behind the brushes, though, it’s a Chop the Head achievement.

Throughout the duration of Contacting, Sunmundi sketches drafts and generates his Book of Genesis; “a New Testament,” he says on “AirDrop,” that’s been “revised, fermented, and [is] bubbling over.” Existing scriptures are outmoded, decoded to death, so on “Sundial Timex” he announces that he “might engrave [his] next verse over top the Rosetta Stone.” A new Genesis—a Neogenesis—is necessitated by how “mankind been picking fights, igniting shit, and fucking this world downward doggy,” as he ferociously raps on “Dawn of Time” over distorted Super Mario Bros. coin chimes.5 “Since day one,” he says, “Adam and Eve been buggin’ to kingdom come.” But he anoints God a “catfish” and pens Adam as a bottom, probably pegged, on “98 ’til Infinity”: “Eve fucked Adam, the bed rattled, / After the whole debacle a bottle of apple liqueur was found in the tabernacle, / The snake tattled.” He confesses that “even the author baffled.”6 But I suspect a clarity of vision. Sunmundi “read[s] the verse off a AI-generated script” that leaves “green digits all over [his] shit.” These songs are creation myths sprung from the lustered loins of motherboards. Finding “divine beginnings and simulation theory” to now be the “same diff.” Sunmundi guides us “from Original Sin to Modernity’s synergy.”

////WORLDSTAR-TEKNOHELL INDUSTRIES////

I’ve previously identified the teknohell on ELUCID’s REVELATOR (2024), defining it as a maximum-security prison of irrational technology use—a soundtrack of staticky swells. Sunmundi locates the teknohell as scam central,7 as WORLDSTAR; precisely what Neil Postman—who Sunmundi has cited as an influence on the album—warned about. Stewart Brand, trippin’ balls in 1966, thought it worth the world’s while to petition NASA for a snapshot of Earth from space. He believed it would activate a unity so intense that it would make any ol’ Human Be-In appear banal. But an ATS-3 photograph of our planet wouldn’t result in all of Earth’s inhabitants holding hands and singing “We Are the World.” If anything, we chose instead to partake in a collective fixation on the black vacuum of surrounding space. There we were, in the blackness, clearly illustrating—word to Walter Vinson—that the world gone wrong. Our last best hope might’ve been Tim Berners-Lee’s World Wide Web, fractaled with hyperlinks, but all superhighways lead to malware and multifactor authentication failures after all.

So Sunmundi’s WORLDSTAR is nothing less than worrisome, is everything worse than we thought. His conception of the WORLDSTAR—again, what I call the teknohell—is Earth itself, or the simulacrum of Earth reflected in each bodega CCTV, or the notorious website of the same name that reflected society at its most awful as caught on fuzzy flip phone footage (a study in woefulness, if ever). Sunmundi sneaks a peek at his own reflection in “the grainy security camera” like woods entering the corner store on “spongebob” (2019) to get the “five-dollar phone cards.” But communication is inevitably ill, and that “overseas connection choppy.” As for Sunmundi, he’s the “black Wally wearer,” observing himself being surveilled. “I got paranoia in every public area,” he says, so he resorts to untraceable means of communication: “The smoke signal is my choice of wireless carrier.” One hopes the smoke obfuscates the lens eye, but even still, he’s carrying a spy on his person. ELUCID told him about the “worldwide PSYOP” on Armand Hammer’s “I Keep A Mirror in My Pocket,” and Sunmundi sees it the same way: “Black mirror damage hurts more than scraping your hands on broken glass.” But even if he repeatedly breaks the glass and leaves splinters & fragments & shards everywhere, he can’t curtail the teknohell: “I restart the game every time I step out my apartment and put the suede Clarks on the street.” Frustrated, he’ll “spit the phlegm on the streets,” like Nas when he told us the world was his (but that 1994 world was no WORLDSTAR). Nas’s world had less complexity, and all that it required was the suede Timbs on his feet to make the cypher complete.

Like woods making those overseas calls, Sunmundi knows when the “connection gets choppy” on “The Whole World (SOS),” a song-as-diagnostic: “The patient presents with multiple malfunctions.” M-U-L-T-I-P-L-E. The imperial apparatus, Hardt and Negri wrote in Empire in that pallorous beforeworld timeline of the year 2000, “is faced by multiple complex variables that change continuously and admit a variety of always incomplete but nonetheless effective solutions.” Sunmundi, seemingly, can name them all.

“I sat down to unwind and time sped,” he says on “Interference (Out the Loop),” as he finds himself insomniacally up and finding unwound to be a formidable Challenge for a Civilized Society. He can’t starve himself from the feeding tubes of coaxial cables, can’t abstain from the scrolling (doom- and otherwise); the cells are fully integrated: truly operating on a cellular level. End result: he’s a “prisoner at home” in teknohell captivity.

In the teknohell, on the WORLDSTAR, time is money; money, time. Communication comes at/with a cost. “Everything I see today filtered through the philosophy of commodified time,” he raps, with that fake-ass filter and pseudo-philosophy riffling in his verse like a bill counter counting bills. “Ad space is the place where Big Brothers bond, subscribe, and align,” he says, sounding like Sunmundi Ra. Sasco makes hypeness happen with only hi-hat taps and Nextel chirps—it’s his free-spazz.

Sunmundi’s geotracked (“my location is no longer mine”), followed, with its strong suggestion of subservience. Suddenly, after some clicks, swipes, and even only the slightest steadying of the eyes, the “commercial knows [him] better” than he knows himself. ELUCID felt that magnetic field throb of a virtual metal detector, too: “I feel a way about proving my identity to robots.” [Sunmundi and ELUCID both should be situated on some Revenge of the Revenge of the Robots tour 2026.] “New fear unlocked,” Sunmundunny says on “Spirit Ballistics” as a lumbering, atonal loop braces for a drum burst, “hopping the turnstile and immediately getting clocked by a vigilante NYPD RoboCop.” The entire technofascist terrain is terrifying, which is why Buckshot once talked of maintaining an outlaw essence, an endless drive, in the face of the modern city’s future-threats: “I got dough, but I still hop the train.” He intended to make a powaful impak!

The WORLDSTAR is full of illusions of choice. Offerings in the offing that amount to nothing—a negation of possibilities. Sunmundi lays out several examples on “AirDrop”: “Blue and red, Pepsi and Coca-Cola, / Who better? Nicki or Doja?” What do you want?!!!??! Capitalism or barbarism?

“I think pornbots are my only fans,” Sunmundi says in the first half of “Algorhythm / Power Lines,” a cute & clever pun that makes light of how [tekno]hellish a DM inbox can get. Jouquin Fox joins him on the second half of the track, introducing himself as a “citizen of the universe: F.O.X.” This is Co Flow’s “Krazy Kings” for the very latest stage (4) capitalism. Together, they tackle androids in a Pharoahe Monch manner, making those Nexus-6s and such “say ow like number 55 on the Chargers,” preserving the CTE’d brains with gunblasts through the sternum. Together, Sunmundi and Jouquin Fox enact a 3rd Bass rewrite. “Pop went the abstraction and every weasel left the premises,” Fox raps. Trading bars, the eMCees stave off ChatGPT psychosis and the ELIZA effect at every turn of their web browsing. “PSYOPs, racist chatbots, evolutionary coding,” Fox rattles off. “Every new follower a sexbot.” Affection and attention not real but manufactured. “Dissect the dialect,” Sunmundi instructs on “Sundial Timex,” corresponding to 3rd Bass’s Derelicts of Dialect. “I clicked the toxic Bandcamp link and caught pop-ups,” but that’s not the only threat, the only ruse. The shit borders on abuse. “The XXL writer’s a bot, fire emojis in your DMs, / For a second there he really had me thinking,” he confesses on “Off the Ontological Strength.” Jouquin Fox is really the mirrored, mimeo’d, equivalent for Sunmundi on this topic. Recently, on “What’s this all mean to you?,” Fox let off a litany of lessons unlearned and advocacy lacking over a Margaret Mouse confabulated flute sample that belies the urgency of the message: “They have my face from A.I. data scraping out selfies.” And on “MADNESSSUITE,” Fox warbles over shemar’s wounded loop, not even willing to feign surprise at the shape of things to come: “The way that this life could go, you can’t get comfortable…can’t get comf-tah-buhl.”

All told, Sunmundi doesn’t wanna be one of the “motherfuckers [who] walk the museum too briskly,” as he raps on “Bright Moments.” He wants to walk at a leisurely pace, enjoy the silence, and prioritize life’s processes. “Aspiring to live low-vis,” he says on “Clout Spells,” “off-grid like an android in the hands of neanderthal pariah.” A “Meditation App” is oxymoronic on its face, as any application ultimately equates to dissonance & distraction & sends mental health downward spiraling.

////THIS GLITCH = GIFT + CURSE////

The great debate…

What came first: the vocal take or the SM58?

—“Meditation App”

Like it or not—knotted tummy; grin and bear it; resigned to the times we live in—the totalizing capitalism realism we [w]reckon with can only, really, be dealt with through heedless hacking. Sunmundi knows this; he does it on the subtle. He’s quick to hack the algorithm into algorhythm; hack power lines of electricity into electrifying powaful lines of song. He did it on “Algorhythm / Power Lines” when he talks of how he “cracked the Earth open” and found it to be “all chrome.” If he can crack it, he can hack it, and Contacting, no question, is Sunmundi and Sasco sitting on top of the world [Walter Vinson in the wings again], sittin’ on chrome [à la Masta Ace Incorporated], and ultimately burning chrome [William Gibson waves hello from cyberspace]. Kitasavi’s chromed-out cover art8—like an e-waste scrapyard meeting a deep puddle of T-1000’s mimetic polyalloy—perfectly renders the entropic explosiveness of Sunmundi rending Earth apart at the longitudinal and latitudinal seams.

The WORLDSTAR, the teknohell, is surveilled, digitized, databased, and what must Sunmundi use in order to authentically document this domain in his art? Digital tools, of course. We’re all inseparable from technology (Gibson calls it “post-mediated,” with posthumanism around the bend), but inevitably someone like Sunmundi comes along and makes art by machete hacking the teknohell to ribbon cables and zip connectors. He illustrates how he gets it done on “Bright Moments.”

Sunmundi explains his practice organically: “Word chains enact with rhythm, / Make my music hit like the intangible power of systems.” It’s with that second clause—like gathering chain blocks and blockchains in a single, solitary steamer trunk—that Sunmundi links his process between the Industrial Age and the Internet Age.9 He trusts in the “immediate punch of a sentence,” as any rapper worth his weight in words should. Pugilistic moments, as Earl Sweatshirt said on “OD” (2019). The sentence, which Garielle Lutz famously called the “loneliest place for a writer,” allows for any and all possibilities when consciously crafted. Lutz describes a good sentence as “flutter[ing] this way and that in playful receptivity,” as in a process of “intimate mutation and transformation”: “…the words swap alphabetary vitals and viscera, tiny bits and dabs of their languagey inner and outer natures.” The teknohell is an inherently lonely place, but the sentence and the song’s consecution (in a Gordon Lish sense) can all but forge the desired social connections. “The task to think large, though we all infinitesimal,” as Sunmundi says. On the humble, but understanding the strength of the song’s permanence: “My death won’t be history, / But I hope my life’s bright moments shine on you exponentially.” That shine lends itself to a shared experience.

Sunmundi is from “the era of the compact disc but still an internet kid,” as he tells us over the Sasco subtleties of calculated keys and teknoheavenly harps on “Disc Comfort (Glitch Pt. II).” As such, personifying the influence of technology on his work is inescapable. But disc comfort is no comfort at all; it is, as its titular pun implies, a discomfort. Perhaps no phrase better sums up Defrag Rap than Sunmundi’s “me and my glitch,” establishing an intelligible lineage to hip-hop’s origins (in this case, Biggie’s “Me & My Bitch”) while also absorbing that influence through a teknohell prizm. Something corporeal and disembodied at once—chest out & decapitatory. Sunmundi is trying to avoid what RAMA invokes on “Spirit Ballistics,” namely, “these wack-ass rappers [who] make careers out of Google Analytics.”

On “Idling Nowhere,” it becomes apparent that Sunmundi sees rapping as a holy act. But even as he “walk[s] on water,” the music turns to “quantifiable metadata.” Short of relying solely on beatboxing and cafeteria tables, hip-hop needs digital tools—the artform is indebted to some of the finest devices to emerge from the teknohell. Sunmundi’s self-awareness disallows any overtaking of his humanity, though. His reshaping of the WORLDSTAR won’t permit any desecration of that which he holds sacred. “I close my eyes humming the hymnal,” he raps, and we can hear the yogic meditation in the consonance of the mantra: hummm & hymmm. He understands that life oftentimes appears to have “condescended into a Druski sketch,” which shows he’s cognizant of competing with absent minds and abbreviated attention spans. As if to grab the listener’s attention, Sasco mutes the beat as Sunmundi emphasizes the Power of the Word: “I’mma go back in time and transcribe It Was Written on papyrus, / Enable cavemen to produce on Ableton and drop real fire.” “In the sanctuary of your caves,” Jeru rapped in ’94, “white kids press record,” but the Damaja never could’ve fathomed the streamlined integration of downloadable DAWs.

On “Sundial Timex,” we find Sunmundi coming home “with a bone to pick,” classical guitar eked thru blown-out glitch, and he easily “transmit[s] that bitch right through the microphone, / [And] the XLR connect the wavy words the SM58 collects.” As he mentions on “Algorhythm / Power Lines,” the problematics of a get busy-via-get digi workflow include creating some “shit [that] make your whole hard drive jam,” absolutely (and don’t forget to back up your work to at least one terabyte external and store that shit in an anti-static bubble bag for safekeeping), but the pitfalls don’t outweigh the pluses. “These power lines like lesson plans for the class of 3005,” he claims, getting Deltronik once again. The equation is clear: his power[ful] lines of lyrics function like power lines of electricity; Sasco’s waveform peaks like the transmission towers supporting his signal.

“This language is the only haven I have and I won’t dial it back,” Sunmundi says on “Meditation App,” hacking the mechas, the mixes, the modems, and the cells which all fashion their own dial feature. Sasco channels a ballistically altered George Benson on the beat, affirmatively. Meanwhile, the cadence and color of Sunmundi’s phrasing—“the only haven I have,” for instance—cuts through the distractive and disconnector noise that Sasco has called a “haze.” Sunmundi’s words move through the pixelated portal10 just as they move through him. He’s the conduit “just reporting what [he] was whispered from a shaman,” as he mentions on “Idling Nowhere.” His cohorts, his peers, are privy to the same procedure of transmutation where thoughts | feelings | suspicions | et al. are energies given voice through an eMCee vessel. Nakama., for example, positions himself as “your friendly neighborhood cognitive conduit”; shemar invokes much the same on “Clout Spells” (“Speak with the conduit, / Ouija board story glow”). Sunmundi, in a verse that follows shemar’s, talks about how he “either speak[s] with the conduit or don’t do it.” Nothing forced and nothing falsified. These eMCees are conduits between the spirit and the SM58, the monitor and the masses. The electrical conduits hacked for South Bronx park jams; the spastic trance-dance séance conduits of Crowley and Cayce; slackening mic cables for strangulation on loan from Conduit of DC Comics, OD’ed on ohms. “The need to be heard, felt, seen,” Sunmundi raps, verbs stacking, “burns like no other.”

A polished, refined conduit (think the flawless shine of Mike Oldfield’s bent bell) builds space for other sensations. Sunmundi, unadulterated by the heavy touch of the teknohell, can allow his pen to allude to The Iron Giant and “Jack and the Beanstalk” both, while fee-fi-fo-fumming in a manner Redman did on EPMD’s “Hardcore” (1990), y’know, he flows some more pro shit. He caricatures himself as “Bugs Bunny holding the Tommy gun,” evoking an image akin to what anarcho-surrealist poet Franklin Rosemont explicates in the essay “Bugs Bunny and Dialectics” (1976). Rosemont calls Bugs a “more or less urbanized descendant of Br’er Rabbit” who is “categorically opposed to wage slavery in all its forms” and represents “a veritable symbol of irreducible recalcitrance.” The image of Bugs Bunny armed to the buckteeth as proof that “someday all the carrots in the world will be ours” (for certain, Phiik & Lungs would concur, what with last year’s Carrot Season propping up what Dash Lewis calls their “goopy, psychotropic” sound). In aggregate, these artists are, as Sunmundi says, “boom bap’s prodigal if not rebellious sons.”

Furthermore, Sunmundi speaks of holding his “album’s listening session” in a “liminal space,” a parlor between the real world and the teknohell where fairytale talk can take root. “I’m outside Goldilocks’ spot holding up the boombox,” he says on “AirDrop,” proving, in shemar’s words, that he too is born made for boombox resting atop doomsday clock, but with Cusack swagger to boot. “I need art,” Sunmundi insists, “like healers need memory, believers need entities, and the world needs energy.” We take him at his Word because his words possess that eager, beseeching quality, which is articulated by the repeated /ē/ sound in the bar. There could be no other motivation. As he raps on “Interference (Out the Loop),” “I can’t equate art with c.r.e.a.m.,” before admitting that “having dreams requires a decent place to sleep.” So he rewrites O.C. Where the one-time Crooklyn Dodger instructed, “Of course we got to pay rent, so money connects, / But, uh, I’d rather be broke and have a whole lot of respect,” Sunmundi surmises, “Rent is rarely cheap, but it’s free in my head, / And the tenant is something I should keep tentatively discrete.” The economics of art, sadly, hasn’t shifted much in twenty-odd years. On “Ethical Hacking,” the dissonance between the two—heightened, perhaps, within the digital domain—has Sunmundi exorcising thoughts of ephemerality: “Almost deleted my whole discography the other day.” Cymbals/symbols crash while a woodwind wheezes its last breaths, even flatlining at a point. Nowadays, nothing seems permanent; everything feels easily erasable.

////PATCHWORK BOY////

Who spiked the humanoid prom party punch?

—“Idling Nowhere”

Everybody’s spirits are under control,

computers run with the soul.

—Deltron 3030, “Turbulence” (2000)

If his art is inseparable from tek, then Sunmundi is, as Rakim once said, a microphone technician. He’s a cyborgian Borges lost in the stacks of his own Library of Babel, late fees flitting in the forced air. The cyborg represents a “coupling,” Donna Haraway writes, of organism and machine. By this time in our history, “we are all chimeras, theorized and fabricated hybrids.” The cyborg, she explains, is “oppositional, utopian, and completely without innocence.” William Gibson coined and clarified the vision of a cyberspace only after witnessing 80s kids slouched over Space Invaders, Galaga, and Centipede.

My observation of the body language of kids playing those early plywood-sided arcade games… I saw the kids playing those games, and I knew they wanted to reach right through the screen and get with what they were playing with there. And I thought, “Well, if there’s space behind the screen and everybody’s got these things at some level—maybe only metaphorically—those spaces are all the same space.

So it makes much sense that Contacting—a hypertext, a cybertext, a work of e-lit—takes time to reflect on the halcyon days of Sunmundi’s youth. On “Disc Comfort (Glitch Pt. II),” video game console and body|mind|soul integrate through recreation: “Double Dash, Super Smash, button mash, / Passing the controller back to back in between turns thinking about the effect death has / And if the soul really lasts.” Whereas the kid in woods’ “a day in a week in a year” (2019) was only “fuckin’ with the joystick, pretending” to be “really playing,” dropping the wisdom of how life’s “just two quarters in the machine, / …either you got it or you don’t,” each rapper grapples with a certain disc-omfort. For woods, it’s “still hittin’ the buttons” as you see “GAME OVER on the screen”; for Sunmundi, existential dread drips from the optical discs.11

Still, though, the fear is a cyborg slide into full machine integration—a loss of senses, human sentience, or Self. “Every drone grew up, lived his life, and died out along with its kids,” Sunmundi says, which should unsettle any screen-starer. On “Interference (Out the Loop),” full integration and an anatomical obsolescence feel like destiny. Sasco’s glock[17]enspiel and phase shifting filtered through telephonic samples do the trick, too. His steez what one of his instrumental tracks imply: “EMP”—an electromagnetic pulse with the requisite spectral surges. Sunmundi catalogs his corporeal state:

My phone, my bones,

tones ring in my head…My screen, my eyes…

I am my clone’s clone.

To be a clone’s clone—a reproduction of a reproduction; a Platonic ideal xeroxed to a grainy ditto of zeros & ones—is a disquieting notion. As Cleofis Randolph the Patriarch said from the Deltron command center, you should want nothing to do with such “homogenous clones.” The tautology begs to be taught. Otherwise, the organism suffers under the cybernetic grip. Sunmundi demonstrates he’s made it through the exploded end of the circuit:

In the past, I let possessions possess me,

it’s a mindfuck being owned by the only thing that gets me,

wrapped around my head; we’re close but not friendly—

wound, exit, entry—mouth closed, predictive text stay ready.

You better call and correct me before this whole shit get messy.

But his ultimate survival, explained on “Idling Nowhere,” is contingent upon the aspects & angles of his non-cyborg self: “My basic needs are water, shelter, and MM..FOOD.”

As he mentions on “Burnt Sugar (Shortcomings),” he’s a “glitched-out son” whose “motherboard got hot.” Sasco’s a conductor of Sunmundi’s conduction. Together, they study This Heat; measure its temp on “AirDrop”: “Who switched my wires and caused fire to the motor?” He was at the point of speaking in buzzes and bursts of acronyms, as he did on “WORLDSTAR”: “My POV only MP3, heights MVP, lows NPC.” Like being reduced to a rush of letters across a chyron. We see it even on the album closer: “Sent the SOS over AOL.” AOL? The distress signal has been getting sent for a long time now. Difficult to say whether Sunmundi is content or concerned that “the extent of [his] legacy is [his] initials etched in a park bench,” as he raps on “Idling Nowhere.” What he needs to navigate these cyborgian blues and gunmetal grays & brushed chrome [in]conveniences is a power surge.

“Clout Spells” includes periodic maulsoft moments, such as the yawning & yawping of a pitched-down vocal snippet. We find shemar spellling like ELUCID over competing piano loops and a Victor Lewis sample from Sasco’s personal archives. “It’s not enough power,” they growl, feeling disenfranchised, severed, or—as we soon figure out—diminished in death. Power? On “Nostrand” (2022), ELUCID says we “don’t know what to do with it.” Confused but not deflated, shemar calls up familiar lynching imagery in their capacity as our “New Age apocalypse seer.” The “shock value” of “an open casket gun wound” reads like the storied demands of Mamie Till-Mobley.12 “Hung like martyr rope” and “living reduced to orchards, strange fruit” are Dadaist cut-ups of Lewis Allan’s lyric sheet. Corporeal death, though, risks resulting only in digital documentation damned to 404 error codes. “Fun fact on the Wiki page,” shemar caustically raps, “archive the citation.” These are spells as sorcery & disorientation both.

///////A LIGHT IN THE STATIC///////

It’s very difficult to find non-mediated human beings.

—William Gibson (1999)

Paramount to any power of mysticism, or esotericism, or conjuration is the power of keeping contact. Sunmundi values the light of linking. Connections are casually severed just as hyperlinks are darkened and dimmed after a single click (clear your browser cache & cookies). “String out the can up to the sky and I’m ringing the bell,” he says at the end of “The Whole World (SOS),” “my whole life I’ve been contacting you.” You the listener, you the aliens—those who have yet to hear him out. He hopes to be Adopted by Aliens, his Words of Wizdumb the entreaty. Throughout Contacting, Sunmundi sounds off like a Doomsday Prophet, like Orko in ’96, and “98 ’til Infinity” is his Alientro. But his most trusted contact is his life’s companion, his wife. On “Meditation App,” the only alphanumerics that save him are “845 +55 4/19.” “It’s an old area code of mine, an old area code of my wife’s, and our anniversary,” he told ANTII. “I’m ringing ya line,” he tells her, “Hope you hit me on the other side of time.”

On “This Connection (Belongings),” Sasco masquerades as a guerilla warfare-enabled Gershwin. In “Burning Chrome” (1982), the story that established cyberspace as a conceptual framework, William Gibson describes hearing Chrome “scream”: “a raw metal sound,” though he doubts his senses. Here, Sasco presents a rhapsody in chrome and clamor, a randomized access memory clarinet glissando. Sunmundi “woke up next to the sunrise,” which scans as his spouse—a far better awakening than those who stir from slumber and ask Siri how they’re gonna die. He turns to the sun motif, and the light the sun emanates, as a means to maintain non-mediated moments. The album even opens with a voice lecturing on the glories of Ra, adrift in his solar barque. The power of the Sun…the controlling force of all that lives and moves here on Earth…send awesome currents of pure energy charging through the atmosphere. The finitude of the sun’s nuclear fusion feels remote, nearly naught, when placed over Sasco’s avant/rap/jazz/fusion production—an eiderdown stitching together Zappa’s Waka/Jawaka and Return to Forever’s Hymn of the Seventh Galaxy. “This is the light that snuck through the prism,” Sunmundi raps on “Bright Moments” with Rahsaan Roland Kirk narrating incandescently. Sasco’s defrag’d & jazz’d sounds are reminiscent of what emerged from Hprizm’s lab in the late ’90s and early aughts.

The brightest moments are the ones where Sunmundi’s writing sings, and those moments coincide with the crystallization of his kin. “This Connection (Belongings)” is one of several examples of what Paul Éluard called l’amour-poésie. As expected, Sunmundi grapples with the teknohell trappings even as he serenades his love songs.

Made a home and wired it outta telephone lines,

life shared on FaceTime.

This the death of long distance dialing—

I see how it goes when affection is handheld vs. wireless.

This dichotomy of love and technology is an elevation from, an advancement beyond, what Buck 65 and Governor Bolts wantonly put together in 2001 with “Making Love to Your Disk Drive.” There’s no no-good lewd talk of input, output…repeat until the sheet soaks. Sunmundi sees “lights beaming from [her] eyes,” and his sentiment lights up iridescently as he woos with assonantal /Ɛ/ & alliterative l’s:

Your smile lends levity—

I’d endlessly let your letters live on my lips.

When Sunmundi speaks of contacting, he’s speaking of existing in the physical, in the material world (the sun turned on, remember?). Skin-to-skin, not the skins designed for your Winamp player in ’98 or the skins purchased as you wait for the start of Travis Scott’s Fortnite “concert.” Sunmundi’s withdrawal from the WORLDSTAR means “we don’t have to say any more goodbyes—it’s only hellos in [his] skies.” Those countless hellos have him appearing as Helios, the sun god. If Beckett once said, “The sun shone, having no alternative, on the nothing new,” Sunmundi responds back with a Ctrl+Alt version that highlights something new, something we always knew.

He feels messiah-like, especially on “AirDrop”: “Raised right so I don’t stoop lower than turning the other cheek in broad daylight, / Under porch lights I take in everything.” He makes human-2-human connexions on tracks like “Telepathy…,” singing—rather well—about trying to reach you. The song plays like a turndown service where wires get reconnected and Sasco becomes a kid amnesiac with treefingers prepping us on how to disappear completely. All it might take is “the littlest spark [to] catch traction”—that’s what Sunmundi says on “Interference (Out the Loop).” Spontaneity in today’s world—on this spinning WORLDSTAR, this spawning teknohell—is a rarity; we’re constantly dictated | distracted by the mess of tek. But if we hold close to the knowledge that “the sun is the source,” like Sunmundi says on “Clout Spells,” then we can “bathe in spark showers out the outlet, / Smiling wide inside a pile of wires,” our inspirations & intimacies inextinguishable.

Seek out Grouper’s A I A: Alien Observer (2011) for the chill-out room once Contacting’s caterwauling, cacophonizing, ack ack ack subsides. On “AirDrop,” we hear that Sunmundi’s transmitting live from mars, or hopes to: “Sasco, my man, we makin’ jams for all the planets and connecting to extraterrestrial Bluetooth owners.” With warbling, wah-wah’d guitar notes and horns haywire like they were yanked from Aesop Rock’s “Hold the Cup” (1999), the ETs are receptive. “I’m shipping my tape to outer space,” he updates on “Sundial Timex,” “heard they give better deals for artists on promo, / Let the aliens lift the private album link to the UFO from the hole in the ozone.” (He’d be remiss not to refer to this pitch as “The Mother of All Demos.”) Such a scenario would be the idealized TEKNOHEAVEN—the place yet to exist where the technology befits and benefits us all—like the digital utopianism discourse one might find virtually flipping through a scanned PDF of Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog, a stateless, decentralized, Haight-Ashbury harmony hang. In other words, what the internet was supposed to be.

This is my second use of sound system already, but only—and warranted—because Sunmundi and Sasco have assuredly manuf[r]actured a mvtherfvckin SOUND SYSTEM—a systematized sound; a system of sounds; asymmetrical sounds. As for “narcotic,” I don’t mean narcotic as narcotic, for there’s zero dozing with Contacting (though I do mean a sound that spans Industrial Breakdown to Degenerate Introduction), but narcotic as in PainKiller, as in Zorn, Laswell, and Harris jamming scabrously.

Sunmundi also responds to ELUCID’s “algorithm that appl[ies] pressure to achieve desired results” from “Sweet Mickey” (2018) with the track “Algorhythm / Power Lines.”

More on cybernetic organisms in a moment, in a sec, in a blip, in a glitch.

“I was very, very struck reading a diary entry somewhere where a man had heard a Victrola for the first time,” William Gibson recalls. “He was completely traumatized by it. He said that he had heard a ‘voice from hell,’ this undead, hideous parody of the human voice and that mankind was doomed, and how could God let such things be?” Hearing what Sasco has done on “Dawn of Time” will have a similar effect. His high-pitch frequency samples will let you know where your dogs at.

Sunmundi’s Neogenesis persists throughout the album. On “Disc Comfort (Glitch Pt. II),” he deifies himself and his works: “These lines came out my ribs, / I made them in my image.” (Back on that bone business again, note; even behind the bars of his thoracic cage.) And on “Idling Nowhere,” Sunmundi devours fermented fruit and brags about how his music “would bump in Eden and turn up the whole garden.”

The track “Scam Central” sounds like the Korova Milkbar jukebox jammed up in a Def Juxtaposition.

The cover art for Masta Ace Incorporated’s Sittin’ on Chrome actually closely resembles Kitasavi’s Contacting art, in metallic aesthetics if not color.

On “Burnt Sugar (Shortcomings),” he speaks further of his supercharged diction: “Words electrocute with shocking tasers.” Sasco’s beat sounds much the same: orchestrallic & fractured sounds struggling through feedback.

“My favorite room on any floor is the portal,” he reveals on “Bright Moments.”

Sunmundi’s childhood did include a fair amount of grass-touching, though—as noted, his living was hybridized, not wholly subsumed. He nostalgically refers to “memories flickering behind you like basketball cards in the bike spokes,” and maybe—just maybe—he had the hologram “El-P rookie card stuck in [his] bicycle spoke.”

“I wanted the world to see what they did to my baby.”

LONG LIVE SUNMUNDI, PEACE FROM KTT